I do not and will not purport to understand what it’s like being Black in America. While I can empathize with that plight, I have never lived it and thus can’t authentically convey such a life experience.

But I can tell you what I witnessed as a child of the South born just one year before the assassination of John F. Kennedy. I can tell you what I was taught from the “happy slave” narrative to the fabulist tale of the first Thanksgiving between Native Americans and Pilgrims to that grating ditty about Columbus.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, who led The New York Times’” Pulitzer Prize-winning “The 1619 Project” and has now published a book that sold out the first printing within a week in November, framed it best: “ … white Americans desire to be free of a past they do not want to remember, while Black Americans remain bound to a past they can never forget.”

“The 1619 Project” starts 402 years ago when the first ship containing slaves arrived in the British colony of Virginia of what eventually would become the United States.

I spent several years as a child in Richmond, Virginia. It’s the first place I went to elementary school. I would return there for middle school and one year of high school – in between I was in St. Louis, Missouri, and Charlotte, North Carolina – and would end my pre-college education in Memphis, Tennessee, and Greenville, South Carolina.

At every stop, I learned the sanitized version of U.S. history, which glossed over a nascent democracy’s two overlapping genocides of Black Americans and Native Americans. Growing up in the South, I heard that not all slaves were poorly treated and in fact some were happy – a position that forces you to magically forget they were sold into chattel slavery – that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was a menace and that Native Americans were savages. What I know now as an adult is that systemic racism has been baked into our legal, housing, educational, workforce and financial institutions, et al, and we are still willfully entrapped in that quagmire.

Martin Luther King Day became a holiday in 1983. People I knew (and, in some cases, are still alive, as are their children) called it Martin Lucifer Coon Day. That was always followed by a low chuckle, a sound my ears are still attuned to, by someone who thinks he just said something so clever. Dr. King was vilified and hated by the majority of white people when he was alive. He was assassinated by a segregationist. As a child, I heard James Earl Ray applauded as a hero. An epithet I heard adults make instead of swearing were the words, “John Brown!” It was years before I learned why. Brown, an abolitionist leader, was a villain to slaveholders. As a child, I learned he was worthy of being cussed – and his name used to curse a situation as minor as a stubbed toe or burnt casserole. Like I said, it’s baked in.

So much history has been omitted from the education of children that is finally coming to light, including Black Wall Street and the Tulsa slaughter; the “hidden figures” of Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson, the Black women at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), a precursor of NASA, whose mathematical skills helped propel John Glenn into orbit in 1962, the same year I was born, while they worked in a segregated section of the building; Henrietta Lacks, the Black woman whose cancer cells are the source of the immortal HeLa cell line that would underpin medical research and later raised legal and ethical issues for the harvesting of those cells at Johns Hopkins without her knowledge and how to reconcile the truth with her survivors; and the revelation of horrific treatment at boarding schools set up for the forced assimilation of Native American children into white America under the official operating belief of “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.”

The schools initially were run by missionaries and later it became a priority of the federal government in what can only be viewed now as acts of malice. U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a Cabinet secretary, directed her department in 2021 to investigate the schools and their lasting impact on the lives of Native Americans.

The removal of Native American children and the stripping of their history and culture was still occurring in the 1960s when I was making construction paper cutouts in public school in Virginia of the happy Thanksgiving feast. History hasn’t just been omitted; it’s been distorted and falsified.

Racial reckoning has been fighting headwinds for four centuries and finally has established somewhat of a foothold – albeit with fierce and deadly resistance – thanks in no small part in my lifetime to the long-overdue turbulence of the 1960s and the Black Lives Matter movement, which started in 2013 and has picked up considerable momentum in the last several years.

Of course, the refrain now is that reckoning has gone too far, and white people are suffering from the backlash. Their children come home from school in tears about being white, a scenario that seems like a fable. The state laws passed within the past year to outlaw Critical Race Theory for schoolchildren – which wasn’t even being taught in school – are part of the history of distortions and falsehoods. A malicious intent now is to stoke white fear. It’s predictable and effective – and perpetuates the whitewashing of American history instead of the racial reckoning we need to finally move forward.

So, let’s turn our attention to an experience I can speak of with firsthand knowledge – white women in America. The majority of white women, based on the last two presidential elections, voted to maintain the status quo and cast votes for a man whose attacks on women – especially women of color – minorities – especially Mexicans and Asians – immigrants, refugees, LGBTQIA community, disabled and Muslims laid bare the depths of his depravity. That was somehow not a dealbreaker.

Maybe it was to maintain white male patriarchy because they ultimately benefit from it financially and socially and chose to overlook the ugliness. Maybe they bought into the fear tactics. Maybe they remained ignorant of what was happening. Maybe they became indoctrinated by propaganda masquerading as news organizations. Or maybe they were just who they always were.

So many times, I have heard in reaction to one atrocity after another in America from Charlottesville to Charleston to Pittsburgh to San Jose to Minneapolis that this is not who we are. Actually, it’s exactly who we are and have been for a long time. Since, well, 1619.

“The 1619 Project” book and accompanying children’s book, “Born on the Water,” debuted at No. 1 on The New York Times bestseller list in non-fiction and children’s book, respectively.

The author is originally from Waterloo, Iowa, and a story of her homecoming can be read at wcfcourier.com/news/local/education/former-teacher-pulitzer-prize-winning-student-meet-onstage-at-west-high-school. One teacher-led to Nikole Hannah-Jones embarking on a path that ultimately led to “The 1619 Project.” Be that teacher. Spark that change. Do so against incredible odds.

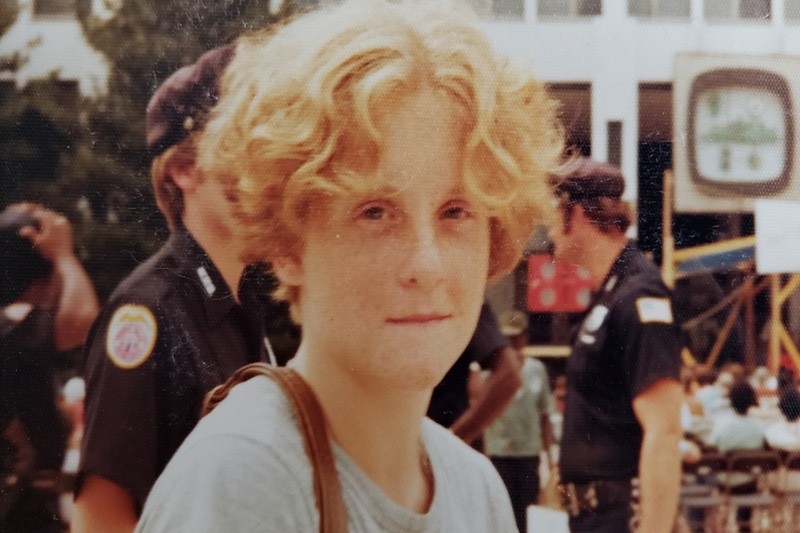

My refuge as a child in every city I lived in was the public library. I would get there on foot or by public transportation or a car ride by my mother. I was fortunate to have a mother who encouraged me to read and learn. The book she gave me to read that had the most impact was “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” by Maya Angelou. She also encouraged me to write. A soundtrack of my youth was the keys clacking on my mother’s typewriter as she wrote short stories.

The last week brought two verdicts that resonated across the country – the acquittal of Kyle Rittenhouse in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and the convictions of Travis McMichael, Gregory McMichael and William “Roddie” Bryan Jr. in Brunswick, Georgia.

The reaction by a few select members of U.S. Congress to the Rittenhouse verdict is a case study in white supremacy, intimidation and racist dog whistles. Had the shooter been Muslim or Black and gone armed to a Trump rally, shot people and claimed self-defense, he would die in prison. He certainly would not meet a former president, be heralded as a hero and be offered an internship in Congress. That Rittenhouse’s victims were white is not the point. They had the audacity to protest for Black Lives Matter. For white racists, the victims became the enemy.

The verdicts in Georgia would never have happened if not for protests when a video of the killing of Ahmaud Arbery became public – the same video law enforcement had viewed already and didn’t file charges – and the exit of two prosecutors on the case. A jury that was nearly all-white returned the guilty verdicts – proof that the South can show the way for racial reconciliation. But it’s going to take a lot more of us.

So, what am I thankful for this Thanksgiving season? Cell phone video. Without it, George Floyd’s killer is never charged and convicted. Arbery’s killers are never charged and convicted. Some of the terrorists who attacked the U.S. Capitol and documented their participation are never identified and charged.

Growing up in the South has both shaped me in wonderful ways and left me seething at what I have seen and heard. Because I am white, I have been mistaken throughout my life as “one of us.” I have been told racist jokes to which I ask for an explanation and am met with silence and the realization that I am not “one of us.” I have been called a n—– lover for not falling in line with racist tropes. I was once told by a white man that “I like you, but I can’t figure how you believe the way you do.” He knew I was raised in the South and had an expectation of how Southern white women should think – and, to be honest, defer to men. Clearly, I didn’t fit the mold.

I also know I have benefited from white privilege my entire life. It doesn’t mean I didn’t work hard or earn my education and jobs. It does mean I had doors open for me that would shut for a minority woman. It does mean I can walk in a store and not be profiled by security. It does mean I can see blue lights behind me and wonder how fast I was going instead of freezing in fear. It does mean I can pass freely in so many situations that would create suspicion for a woman of color. It does mean I am in the majority in all the places I have lived and worked and have never felt the discomfort of being different. (Minus being gay in the Bible Belt, but that’s a column for another day.)

I was raised, too, to not make a scene. This was, of course, the 1960s and 1970s, and girls were restricted in so many ways and confined to roles. (I wanted to be a Cub Scout, altar boy and play Little League; none was an option.)

As an adult, I will make a scene. I will not sit silently in the company of racist people for a holiday dinner. I will not go along to get along. I need more people, especially white women, to speak up. If you see something, use your voice. If you hear something racist, challenge it. If you witness something, record it. If you can, stop it. White people need to check other white people. You have the power to change the narrative. Someone needs to hear it. Someone is hurting. Someone is vulnerable to violence. Stand up. Take a stand.

Make a scene this holiday season. You might save a life.

Maria M. Cornelius is a writer based in East Tennessee.